Note: This was part of what was intended to be about a book-length write-up of all major Dracula movies/shows/media that I made fair progress on before getting sidetracked by real-world horrors. Still, I was always very happy with this write-up of the original Nosferatu, and on the eve of Robert Eggers’s new remake, I thought it would be an appropriate time to share it with the world. And no, unfortunately I never made much headway on writing up the Herzog version(s), so don’t look for those. Enjoy!

By Jonathan Morris

There is always a clear dilemma in writing about a film that has been analyzed to death, and then to undeath, and then back to death. Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror has been the subject of books, doctoral theses, articles, essays, YouTube videos, and countless movie reviews – almost none of which assess its quality because how could you even do that? Directed by the great F.W. Murnau, Nosferatu is not only a landmark of Horror cinema but of global cinema, a maturation of the German Expressionist movement into the broader realm of mainstream filmmaking, and perhaps the most widely viewed silent film of the post-television era (and among the most influential). To call it “bad” would be to label oneself an ignorant fool of deficient taste. Instead, many have tried to mine its imagery and narrative for symbolic representation, and heck, more power to them. For me, however, I’m going to do something a bit different.

In short: Fuck this movie.

Allow me to explain: All of us have something in our childhood, usually a movie, that just scared the ever-loving bejesus out of us in a really big and sometimes bad way. Something that, once seen, haunted our pre-pubescent psyches so badly that it kept us up nights, made us afraid of looking under our beds and into our closets, and caused us to run into our parents’ bedrooms at the slightest provocation. For me, that happened when I was 8 years old, and that film was Nosferatu.

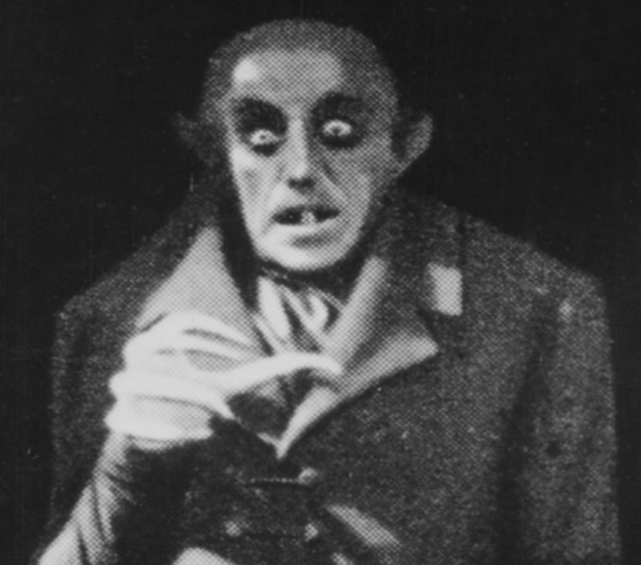

When I first saw it, I was well into my monster fandom and had already seen Karloff’s Frankenstein, Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera, and even Lugosi’s Dracula, and I was a big geek for all of them. As such, my father felt little hesitation about letting me stay up late on a Saturday night to watch Nosferatu on a local PBS station. In retrospect, it wasn’t the terrifyingly verminous visage of Max Schreck’s Graf Orlock (as the film’s Dracula was called) that really filled me with terror (though – and let me be clear on this – that DID NOT HELP), it was what the film did with shadows, particularly the famous shot of the vampire’s silhouette ascending the staircase at the film’s climax, that ultimately did me in. For literally months afterward, I was scared to go into my hallway late at night because the moonlit shadows that illuminated the staircase just outside my bedroom filled me with dread. I also began making it a point not to drink anything for two hours before bedtime, because running out to the bathroom in the middle of the night suddenly required more courage than I could typically muster.

Hell, if I’m being completely honest here, I even had issues nearly into adulthood about sleeping with the door to my room open due to the sequence where the Nosferatu walks in through the Harker character’s bedroom doorway, and it took owning multiple dogs for me to really ever get over it. So yeah: FUCK THIS MOVIE. It’s the only horror move I’ve ever seen that not only scared me but traumatized me, and it owes me more hours of lost sleep than could ever be repaid.

Don’t misunderstand me, though: I love it, too, and the fact that it remains that one movie that was able to play and prey so much on my terror has earned it my undying respect. I was eventually, finally, inevitably able to start watching it again when I was a teenager and have easily seen it dozens of times, and I credit it with engendering my interest in silent cinema and my near militancy towards anyone who tries to dismiss those films as archaic and ineffectual.

Now, as I’m sure you’ve already heard or read many times before if you’re reading this now, this was the first full – albeit totally unauthorized – film adaptation of Dracula, and due in part to the film’s producers, Prana Film, not having obtained official approval from the widow of Bram Stoker to actually adapt the novel (more on that in a bit), it made some departures from the source material, beginning with the names of characters. Count Dracula here was renamed “Graf Orlock,” Jonathan Harker was renamed “Thomas Hutter,” his wife Mina was renamed “Ellen,” Professor Van Helsing was renamed “Professor Bulwer,” Renfield was renamed “Knock,” and the main action was transposed from London to the German port city of Wismar, here renamed “Wisborg,” presumably because someone said, “Fuck it, we’ve renamed everything else.” As mentioned before, the film’s vampire, played unforgettably by Max Schreck, was neither the proud aristocratic predator nor sexy beast of the novel and numerous later adaptations – he was instead Death incarnate: a grotesque monstrosity with rat-like facial features, raptor-like talons, and spidery movements and mannerisms who bore the Black Death (better known as the Bubonic plague) and offered no premise or promise of eternal life. Other than that, the story of a powerful vampire moving from an obscure, remote country steeped in superstition to a civilized metropolis remains spiritually intact…at least until its denouement, which goes far afield from the novel but arguably (and I would argue this) ends on a far more poignant and heartbreaking note. It also entered into the popular lexicon of vampire lore the trope that sunlight was fatal to the undead, an idea that was not present in either Stoker’s novel or earlier superstitions. Oh, um…spoilers?

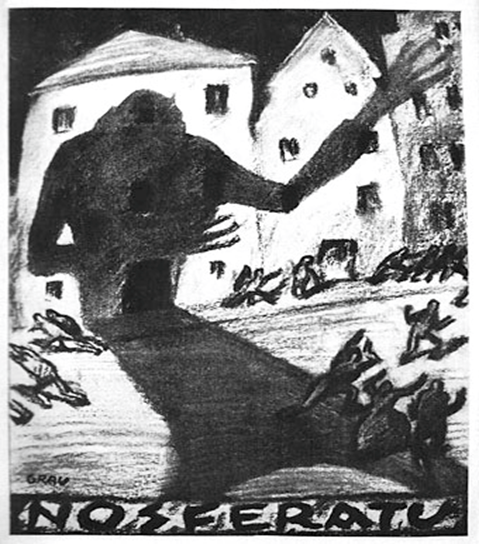

While undeniably supported by its appropriated literary pedigree, Nosferatu remains a visual masterpiece that still stands separate and above all – or at least nearly all – other versions of Dracula. Mixing stop-motion, reverse exposure, highly symbolic framing, and yes, those infamous shadows that fueled my nightmares, Nosferatu features one famous sequence after another, each one arguably spookier than the one before it. While subtitled a A Symphony of Horror due to having what was then the unique idea of having a score written exclusively for the film, Murnau’s film itself boasts a profoundly rhythmic quality to its visuals and pacing, to the point he supposedly utilized a metronome to make sure the actors kept time during their scenes. In a deviation from many of his contemporaries, and despite the film’s fantastical nature, Murnau used heavy location shooting, giving the film a marked sense of naturalism that enhanced its supernatural elements without undermining its Expressionist origins. Besides Murnau’s excellent direction, the film featured dreamlike cinematography from Fritz Arno Wagner and production design from Albin Grau, one of the film’s producers and an artist who had a marked predilection for the occult (he was even rumored to have been a straight-up diabolist). Grau specifically deserves credit for the design and appearance of Orlock and was responsible for some of the film’s legendarily spooky promotional art.

Of course, as mentioned earlier, in an amazing demonstration of ignorance, arrogance, dishonesty, parsimony, or stupidity (and maybe all of the above), Prana Film did not acquire the rights from Bram Stoker’s widow, Florence Bascombe Stoker, to adapt the novel onto film. While the early silent era was rife with filmmakers unofficially adapting other source material – one of Murnau’s prior films, the now-lost Der Januskampf, was itself an unofficial version of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – and despite changing many of the core characters’ names, the filmmakers did very little to hide the relationship between Nosferatu and Dracula. Thus, when Florence Stoker was anonymously mailed the program of the film’s Munich premiere, which advertised itself as a “free adaptation inspired by Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” she had more than ample grounds for what turned out to be a landmark lawsuit, which ended with the still-unprecedented (and thankfully unrepeated) legal order for all copies of Nosferatu to be destroyed. While an absolute nightmare scenario for any film, in Florence Stoker’s defense, she was a nearly-destitute widow in her early sixties when she learned that the film had been produced without her permission. Furthermore, and contrary to popular perception, Prana Film explicitly declared bankruptcy so as to avoid paying her any compensation whatsoever from the film’s proceeds – they were not actually bankrupted by her lawsuit as many have repeated and misrepresented. While her vindictiveness may have been short-sighted – to the degree that she’s sometimes vilified – I find it hard to say that her anger was unwarranted. Of course, this should also be weighed against the fact that of the 20 feature films Murnau completed, 12 are now lost, likely forever; that we could have lived in a world without Nosferatu remains a chilling thought. Fortunately, the verdict proved difficult to enforce and the film did survive, with copies having found their way into many other countries by that point. Nosferatu made its American debut in New York City in 1929, coming off the success of the fully authorized Broadway production of Dracula and Murnau’s critical laurels in the aftermath of his Oscar-winning Sunrise. It was then something of a forgotten entity for several years after that before being rediscovered through airings on PBS and UHF stations in the 1960s and subsequently acquiring its much-deserved reputation as a cinematic masterpiece.

In the world of film studies, Nosferatu is also widely known for having been subjected to a variety of interpretations, many of which are amusingly contradictory but which have also been known to add to the film’s menace and gravitas. Former Weimar era film critic Siegfried Kracauer, in his seminal but now often-disputed tome From Caligari to Hitler (1947) credited Nosferatu, with its story of a monstrous figure preying on an unsuspecting populous, as being among a series of films of the era that presaged the coming of Hitler and the Nazis (for the record, I don’t actually believe that, and Kracauer’s book is often held up as a notorious example of someone imposing their interpretations on films in the absence of evidence and accurate context). Certain queer scholars have also looked at the film as representing high camp and sexual stigmatization (deriving in part from Murnau having been gay), and some psychoanalytical scholars have gone so far to state outright that Schreck’s Orlock was meant to personify an erect phallus because, well…why wouldn’t they do that?

The one interpretation that has the most purchase nowadays, regrettably yet understandably, is the possibility that the film may have been intended, one some level, to be anti-Semitic. Many observers have remarked that Orlock’s rat-like appearance was similar to later anti-Jewish propaganda in the Nazi era– which is sadly true – and that the film’s narrative of a rich, Eastern European monster invading a picturesque German city, spreading the plague, and victimizing a wholesome German woman was trying to play on the fears of economic displacement, cultural death, sexual miscegenation, and the infamous “blood libel” that were, and sadly still are, major defining traits of anti-Semitic and white supremacist rhetoric. And certainly, there’s a lot of that anti-foreigner and even anti-Jewish bias in Stoker’s novel to begin with. Whether that was a true aim of the film or not remains very speculative, and it’s very possible that both the film and the later Nazi propaganda drew separately upon shared archetypes. Henrik Galeen, who wrote the film’s screenplay, was himself Jewish (though not Eastern-European, as were many of those specifically targeted for scorn by Weimar-era anti-Semitism), and of the film’s chief creative personnel who lived to see the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s, only the film’s leading lady Greta Schroeder and its cinematographer Wagner actually remained in Germany for the duration of the war. Regardless of whether the symbolism was meant to be read that way by the filmmakers, consciously or unconsciously, the image of Orlock has been too-often appropriated on the internet by Nazis and the alt-right as representing the “predatory Jew” or “blood libel.” (Sigh.) As said, however, I myself saw it many, many times before this symbolism was even made clear to me…it never encouraged or engendered those beliefs in me nor left me thinking of them as anything other than abhorrent. I believe it can be watched without those interpretations, and obviously should be, whether they were its creators’ intentions or not.

Whatever interpretation one makes of Nosferatu, if indeed you choose to interpret it as anything beyond a vampire movie, I think it’s inarguable that at least some of Nosfeatu both grew from and reflected the horrors of its time and place. And because of that, the film represents history – not only cinematic history or Dracula history but of a a post-war Germany that was doomed to slide into barbarism, a Europe that was still-reeling from the horrors of the First World War, and a planet that was only a few years removed from as many as 100 million people dying from the Spanish flu epidemic. It is a horror film from a time and place that knew well what horror could be. Or, to paraphrase another oft-analyzed remnant from German history, to gaze into Nosferatu is to gaze into history, and you may find, especially on dark nights as the shadows move menacingly on the wall…that Nosferatu may gaze back at you.

RECOMMENDED VAMPING

Released in 2000, Shadow of the Vampire tells an alternate history, behind-the-scenes version of the making of Nosferatu, wherein F.W. Murnau (John Malkovich) hires an actual vampire (Willem Defoe), who he christens as Max Schreck, to play the vampire in his film. It’s not quite for all tastes, nor is it the comedy its premise might indicate, but a compelling horror film in its own right about the excesses of artistic visionaries that features an award-caliber performance from Defoe.

BEYOND THE GRAVE

His Name Means “Terror”

One of the clever concepts that Shadow of the Vampire played with is that, in the pre-internet age, there were a number of urban legends bandied about in fandom circles about the “true” identity of Max Schreck, whose surname is the German word for “fright” or “terror”, and thus left many believing the name to be a really cool and on-point stage name (as in “maximum terror” or something). The most common assumption was that he was another actor under heavy make-up and using the assumed name, or perhaps a genuinely freaky-looking guy who Murnau and company found and was never heard from again. When I was a kid attending a fan convention with my friends, I even sat through a cockamamie theory put forth by an exuberant “expert” that Schreck was actually Bela Lugosi, who legitimately had a bit part in Der Januskampf, Murnau’s earlier film, before emigrating to the United States. While the theories enhanced the film’s mysterious cache for a time, the truth, as it turns out, wasn’t terribly mysterious. There was actually a prominent German actor at the time with the somewhat fortuitous name of Max Schreck, and he was outside of his verminous makeup a fairly normal looking guy who had a very long career as a character actor in numerous German film and stage productions. He even appeared in a later Murnau film, and a comedy no less, called The Grand Duke’s Finances. The real Max Schreck passed away from a heart attack in 1936 at the age of 56, hours after performing onstage.

Symphonies of Horror

As mentioned, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror was one of the first films to have had a score written expressly for it, crafted by composer Hans Erdman. However, the film was produced before film could be synchronized with sound, so no actual recording of the score was ever made to be synched with the film. Only certain written portions of the score still exist, though composers Gillian B. Anderson and Jordan Kessler created a restored version in the 1990s that is commonly used today. Many, many other composers and artists, however, have crafted their own accompaniment to the film over the years, including longtime Hammer films composer James Bernard, experimental chamber group Art Zoyd, and Goth Metal pioneers Type O Negative.

What’s in a name? Part 1

For a film that has been in the public domain for decades, there are many versions of Nosferatu in existence of varying lengths, some slightly over an hour and some closer to the original film’s running time of 89 minutes. As a general rule of thumb, versions that use some of the original novel’s names, like Dracula, Harker, Lucy, Van Helsing, etc., and use the solo title of Nosferatu without its original subtitle may be derived from lower quality 16mm film prints; besides being unrestored, they are sometimes displayed at a slightly accelerated film speed so that they would run shorter on television. They’re better than not seeing the movie at all, of course, but this is a film worth tracking down a restored version. The closest to “official version” is the one licensed from the F.W. Murnau archive that is released by Kino video on Blu Ray and other formats, which included English translations of the original title cards, completely remastered footage, and the restored Hans Erdman score.

The Afterlife of F.W. Murnau

Though best known for Nosferatu, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau was one of the great film visionaries of the late silent age. His later film The Last Laugh (1925), a collaboration with actor Emil Jannings and legendary cinematographer Karl Freund (who also did the cinematography for Browning and Lugosi’s Dracula) was one of the best regarded films of its day due to what was called the “unchained camera,” which saw the camera put through a plethora of motions and into a variety of locations that were simply unexpected from the typically static camera placement in films of the time; no less than Alfred Hitchcock considered it one of his greatest film influences and credited it with forever altering how he perceived the visual potential of film. Arguably Murnau’s masterpiece, however, was his first American film, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), a film about a married couple rediscovering their love for one another after the husband’s infidelity and murderous intentions. It furthered Murnau’s earlier innovations in film scoring from Nosferatu and, though silent, was one of the first feature films to use a synchronized soundtrack and sound effects to incredible, emotional effect.

A week before the release of what became his final film, Tabu (1931), Murnau was tragically killed when his car, being driven by a then 14-year-old servant, crashed on the Pacific Coast parkway in Los Angeles. In his highly discredited “tell-all” book Hollywood Babylon, experimental filmmaker Kenneth Anger made some extremely sordid and highly slanderous insinuations about Murnau’s relationship with the teenager that have entered into the realm of urban legend but have never been corroborated in any substantive way outside of Anger’s book. Much of Hollywood Babylon has been debunked over the years, and, personally, I only mention these insinuations to cast doubt upon them.

There is one genuinely creepy footnote to Murnau’s legacy, however: in 2015, his grave in Munich, Germany was found to have been broken into and his head removed from his body. At the gravesite were traces of candle wax, leading investigators to believe that the desecration occurred as part of a bizarre occult ceremony, with the general assumption being that Murnau’s body was targeted due to his association with Nosferatu. To this day, the perpetrators have never been caught, and Murnau’s head has been neither recovered nor returned…

You must be logged in to post a comment.